What have we found out so far?

Brain activities of parent and child synchronize during play

When we get along well with other people, we are literally on the same wavelength. Research with adults shows that the attunement of rhythmic brain activity plays a particularly important role in interpersonal coordination and communication. When mothers and children play together, do they also show attunement in their brain activity, and which behaviors contribute to this attunement?

In the present study, five to six-year-old children and their mothers either solved puzzles together or individually, just as they might do at home. During the game, functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) was used to simultaneously measure the brain activity of mother and child. fNIRS records changes in oxygen saturation in brain regions that are important for different aspects of cognition and emotion. We measured the brain activity of mother and child in the temporal lobe and frontal brain. Activation in these regions is related to the formation of shared intention, perspective-taking, and self-regulation. These processes are particularly important for social interactions and develop during pre-school age. Our results show that the attunement of the brain activity of mother and child only occurred when both solved the puzzle together, and especially when both responded to each other in a turn-taking manner. No synchronization was found when they separately devoted themselves to the task. Our study shows that the alignment of brain activity plays a fundamental role in social interactions in childhood.

In another study, we found that fathers also synchronize brain rhythms with their children during joint play! This was especially the case when they strongly identified with their role as father.

Even at the age of four to six months, babies can already synchronize with their mothers. The brain activities between mothers and babies adapted to each other especially when they had close physical contact and when the mother frequently touched the baby lovingly.

Infants focus their attention on what other people look at.

When babies are born, they are facing with an incredible influx of new sensory inputs. They first have to organize these impressions in order to find their way in their surroundings. But in what way do infants direct their attention to select the relevant cues from their environment? How do they know what is important?

So far, in our studies we have been able to show that infants follow other people's gaze at objects in their surroundings as early as the age of 4 months. Thereby, their attention is being focused precisely on objects that others are looking at. In this way, babies are better able to remember these objects rather than other objects that happened to be nearby. Therefore, social attention can help infants to focus on relevant things and specifically remember them.

Using eye movement measurements, we investigate how babies' attention can be most effectively directed to objects and events in their environment. We are particularly interested in the mechanisms and developmental processes that lead babies to pay special attention to social cues, such as the eyes or gaze direction of other people.

Eye contact increases infants' attention.

Eye contact is a powerful social cue in human communication. When somebody engages in eye contact with us, we feel directly addressed. And what about babies?

In one of our studies, 9-month-old infants looked at toys on a computer screen together with an experimenter. The brain activity of the children was recorded using electroencephalography (EEG). The experimenter either made eye contact with the child before the toy appeared on the screen, or she looked at the screen all the time and did not respond to the child at all. Although in both cases the baby and the adult looked at the toys at the same time, only previous eye contact resulted in a real shared experience through mutual attention. In fact, this joint gaze between the child and the adult made a big difference: babies reacted with significantly increased attention and brain activity to the toys they looked at together with the adult after eye contact. And so already in this early age, eye contact seems to have a considerable effect!

We now investigate social learning during the dynamic and natural interaction between children and adults. We specifically look at what exactly in these interactions would help children learn something from the adult, for example when learning new words. Is eye contact the crucial factor in this case, or is it rather significant that the adult always reacts promptly to the child? Is it important that the children are familiar with the adult, or do they also learn from a previously unknown experimenter?

Children also imitate seemingly irrelevant actions.

Children learn a lot from other people through imitation, i.e. they simply imitate the actions they see. The advantage of learning through imitation is that children can also learn actions, which they do not yet understand the exact function of. Interestingly, however, children also imitate actions that are obviously not useful or necessary for achieving a given goal.

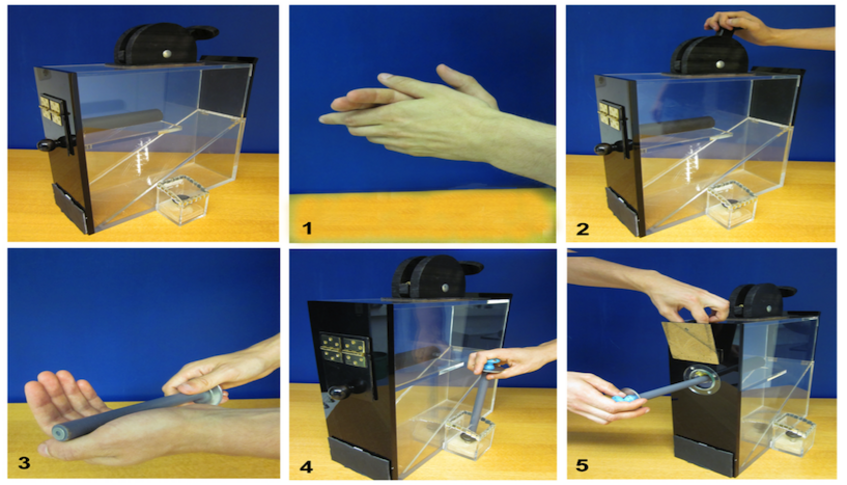

In one of our studies, 5-year-old children watched an adult experimenter take a small reward out of a transparent container. The experimenter did not only carry out the relevant steps but also those that obviously did not make sense. For example, she clapped her hands and pressed a functionless button on the side of the box. Children imitated surprisingly many of these functionless actions, even when they felt unobserved and when the experimenter had not communicated directly with them. This finding shows that children observe other people's actions very attentively and imitate them, even if the actions do not make any immediate sense. This could be because children learn from others not only how things work, but also how to follow social norms and rules. These norms often have no direct function (i.e. shaking hands as a greeting), but are of great social significance.

In a current study, we want to find out whether children are more likely to imitate the actions of people with whom they have played together before, or who are personally close to them. We would like to better understand which factors are conducive to social learning in children.